Air pollution exposure linked to educational outcomes

Credit: Pixabay

It is increasingly widely acknowledged that exposure to air pollution can negatively impact health. A growing body evidence documents detrimental short and long-run effects of air pollution on educational outcomes, which in turn has long-term implications on employment, earnings and other socioeconomic outcomes. Pollutants such as particulate matter, nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxides can impact student performances through a variety of channels, including higher incidence of respiratory illnesses and asthma, lower sleep quality and higher school absences, but also by hindering neurocognitive development, increasing the risk of neurological diseases and hampering the development of the working memory.

An increased availability of fine-grained geospatial data on pollutants and atmospheric conditions from monitoring stations or from satellite-derived estimates allows to assess the effect of pollution exposure on educational achievements at the neighbourhood or school level.

The recent implementation of Low Emission Zones (LEZ) in several European cities, which restrict access to high-emission vehicles in designated urban areas, typically inner cities, has been shown to improve performances in high-stakes tests, to increase the likelihood of enrolling to the academic track in secondary school and to decrease school absences in the areas affected by the policy, in addition to having positive spillover effects in neighbouring areas.

While these studies assess the short- to medium-term effects of this policy at the neighbourhood, school or city level, other studies investigate the long-term effect of prenatal exposure to air pollution on educational achievement, using individual level data. The effects of pollution exposure in-utero are particularly detrimental, since during gestation occurs most of the formation process of the brain and other vital organs. Several studies show large negative effects of prenatal pollution exposure on educational outcomes and school trajectories.

The effects, however, are not uniform across the population: children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may be more affected and more vulnerable, on one hand because low SES families and ethnic minorities tend to be more exposed to air pollutants and to reside in areas with lower air quality. On the other hand, however, low SES families have less means to protect the child from the effects of adverse exposure.

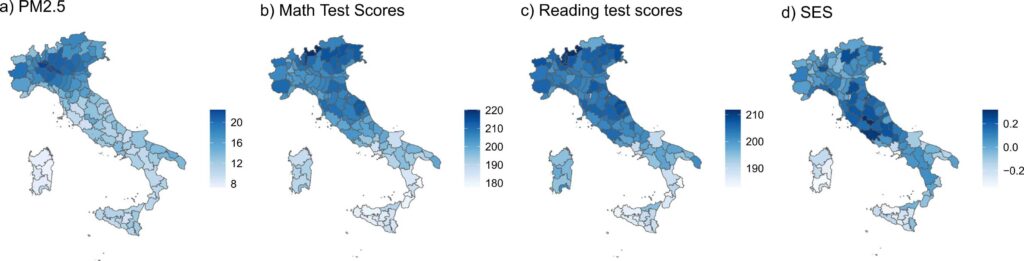

More generally, bivariate relationships of pollution levels and educational achievement may mask social stratification patterns: the figure below illustrates this for Italy, where the northern provinces show the highest concentrations of PM2.5 but also the highest average test scores for national exams in the country.

Fig. 1. Average PM2.5, math and reading test scores and average SES in schools in Italian provinces. Note: in panel a) we report the average PM2.5 values at the provinces included in the analysis measured in µg/m3. In panel b) we report average math test scores at the provinces in Italy. In panel c), we report the average reading test scores. In panel d) we report the average SES based on the standardized ESCS index. All measures are based on values at the school locations and weighted by the number of students in each province. Source: Bernardi & Keivabu (2024)

Our Mapineq Link interactive dashboard allows you as a policy-maker, journalist or researcher to examine and explore similar topics related to pollution concentrations and educational outcomes at the subnational level, thanks to the availability, for all the continent, of granular satellite-derived data on pollutants such as ultra-fine particulate matter (PM2.5).

(Written by Giovanni Scotti Bentivoglio, updated Melinda C. Mills 04 December 2024)