Economic uncertainty and fertility

Many high-income countries have experienced postponement to later ages at childbearing, lower overall fertility and increased levels of childlessness. The reasons for fertility postponement has been explored in detail and related to multiple factors such as effective contraception, women's increased educational attainment and entry into the labour market, work-life reconciliation issues, gender inequality, changing norms surrounding children and multiple types of uncertainty.

Early economic theories linked fertility to the 'affordability clause' or need for individuals to reach a satisfactory income level before embarking on parenthood (Easterlin 1975). A 2005 study developed a theoretical framework linking economic and employment relation uncertainty to fertility postponement, demonstrating it empirically across 14 different countries (Mills & Blossfeld 2005). The central hypothesis, building on Oppenheimer (1988), was that youth found it increasingly difficult to make long term binding decisions about the future like parenthood, particularly in the face of temporary contracts, precarious jobs and a volatile labour market. Others extended this work examining economic uncertainty and fertility in relation to job insecurity, financial concerns or lack of consumer confidence (Kreyenfeld 2010; Brauner-Otto & Geist 2018). Recent work has also highlighted how subjective feelings of economic uncertainty (Lappegård et al. 2022; Vignoli et al. 2020) and societal pessimism are related to low fertility (Ivanova & Balbo 2024). Another study demonstrated that it is not an increased degree of perceived economic uncertainty over time that is driving postponement, but rather that the link between income and first birth has itself gained a stronger positive association over the past two decades (van Wijk & Billari 2024).

....youth find it increasingly difficult to make long term binding decisions about the future like parenthood, particularly in the face of temporary contracts, precarious jobs and a volatile labour market.

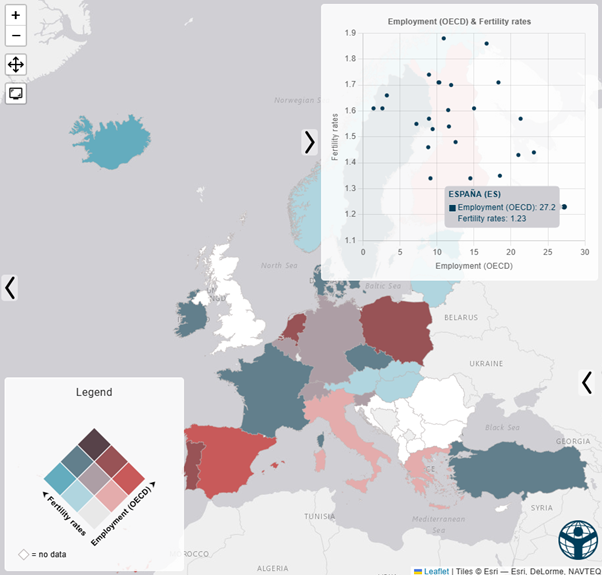

Multiple aspects of fertility can be examined in the Mapineq Link database, relating it to economic uncertainty, but also policies, education and multiple other factors. The Figure below is a screenshot from the Mapineq Link database showing the Share of Employed women with a Temporary Contract (labelled as Employment (OECD) and Total Fertility Rates (labelled as Fertility rates). [Note: this is the Alpha version and we are working on refining the labeling]. The scatterplot in the upper right hand corner highlights Spain where we see a high proportion of women with temporary contracts and a very low TFR of 1.23 in 2019.

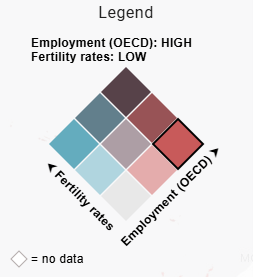

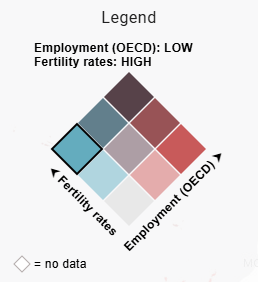

For those not accustomed to reading the bivariate plot in the bottom left hand corner of the dashboard should click 'View Case Study' where you can 'hover' with your mouse over the different categories to understand their meaning. Here are some static screenshots to interpret the bivariate plot legend above.

Here we see that the brighter red colour refers to countries that have a high percentage of women in temporary contracts and low total fertility rates.

The bright blue colour, on the other hand, illustrates countries that have a comparatively low percentage of women holding temporary contracts and a relatively higher total fertility rate.

(written by Melinda Mills, most recent edit 06 December 2024)